Category: Python Tools

Tags: indent, PTVS, python, Visual Studio

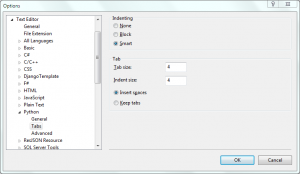

The text editor in Visual Studio provides a number of options related to indentation. Apart from the standard tabs/spaces and “how many” options, you can choose between three behaviours: “None”, “Block” and “Smart.”

To my knowledge, the “None” mode is very rarely used. When enabled, pressing Enter will move the caret (the proper name for the text cursor) to the first column of the following line. While this is the normal behaviour in a word processor, it does not suit programming quite as well.

“Block” mode is more useful. In this mode, pressing Enter will move the caret to the following line and insert as many spaces/tabs as appeared at the start of the previous line. This ensures that consecutive lines of text all start in the same column by default, which is commonly used as a hint to the programmer that they are part of the same block.

However, the most common (and default) mode is “Smart.” Unlike the other two modes, which are built into the editor, smart indentation is provided by a language service (which are also responsible for providing syntax highlighting and completions). Because they are targeted to a specific language, they can help the programmer by automatically adding and removing extra indentation in ways that make sense.

For example, the smart indentation for C++ will automatically add an indent after an open brace, which begins a new block, and remove an indent for a close brace, which ends the block. Similarly, an indent is added after “if” or “while” statements, as well as the others that support implicit blocks, and removed after the one statement that may follow. In most cases, a programmer can simply continue typing without ever having to manually indent or unindent their code.

This feature has existed since very early in Python Tools for Visual Studio’s life, but the implementation has changed significantly over time. In this post we will look at the algorithms used in changesets 41aa3fe86341 and 4db951c455d5, as well as the general approach to providing smart indentation from a language service.

ISmartIndentProvider

Since Visual Studio 2010, language services have provided smart indenting by exporting an MEF component implementing ISmartIndentProvider. This interface includes one method, CreateSmartIndent, which returns an object implementing ISmartIndent for a provided text view. ISmartIndent also only includes one method (ignoring Dispose), GetDesiredIndentation, which returns the number of spaces to indent by. VS will convert this to tabs (or a mix of tabs and spaces) depending on the user’s settings.

The entire implementation of these interfaces in PTVS looks like this:

[Export(typeof(ISmartIndentProvider))]

[ContentType(PythonCoreConstants.ContentType)]

public sealed class SmartIndentProvider : ISmartIndentProvider {

private sealed class Indent : ISmartIndent {

private readonly ITextView _textView;

public Indent(ITextView view) {

_textView = view;

}

public int? GetDesiredIndentation(ITextSnapshotLine line) {

if (PythonToolsPackage.Instance.LangPrefs.IndentMode == vsIndentStyle.vsIndentStyleSmart) {

return AutoIndent.GetLineIndentation(line, _textView);

} else {

return null;

}

}

public void Dispose() { }

}

public ISmartIndent CreateSmartIndent(ITextView textView) {

return new Indent(textView);

}

}

The AutoIndent class referenced in GetDesiredIndentation contains the algorithm for calculating how many spaces are required. Two algorithms for this are described in the following sections, the first using reverse detection and the second using forward detection.

Reverse Indent Detection

This algorithm was used in PTVS up to changeset 41aa3fe86341, which was shortly before version 1.0 was released. It was designed to be efficient by minimising the amount of code scanned, but ultimately got so many corner cases wrong that it was easier to replace it with the newer algorithm. The full source file is AutoIndent.cs.

At its simplest, indent detection in Python is based entirely on the preceding line. The normal case is to copy the indentation from that line. However, if it ends with a colon then we should add one level, since that is how Python starts blocks. Also, we can safely remove one level if the previous line is a return, raise, break or continue statement, since no more of that block will be executed. (As a bonus, we also do this after a pass statement, since its main use is to indicate an empty block.) The complications come when the preceding textual line is not the preceding line of code.

Take the following example:

if a == 1 and (b == 2 or

c == 3):

How many spaces should we add for line 3? According to the above algorithm, we’d add 15 plus the user’s indent size setting (for the colon on line 2). This is clearly not correct, since the if statement has 0 leading spaces, but it is the result when applying the simpler algorithm.

Finding the start of an expression is actually such a common task in a language service that PTVS has a ReverseExpressionParser class. It tokenises the source code as normal, but rather than parsing from the start it parses backwards from an arbitrary point. Since the parser state (things like the number of open brackets) is unknown, the class is most useful for identifying the span of a single expression (hence the name).

For smart indentation, the parser is used twice: once to find the start of the expression assuming we’re not inside a grouping (the zero on line 102) and once assuming we are inside a grouping (the one on line 103).The span provided on line 94 is the location of the last token before the caret, which for smart indenting should be an end of line character (that the parser automatically skips).

// use the expression parser to figure out if we're in a grouping...

var revParser = new ReverseExpressionParser(

line.Snapshot,

line.Snapshot.TextBuffer,

line.Snapshot.CreateTrackingSpan(

tokens[tokenIndex].Span.Span,

SpanTrackingMode.EdgePositive

)

);

int paramIndex;

SnapshotPoint? sigStart;

var exprRangeNoImplicitOpen = revParser.GetExpressionRange(0, out paramIndex, out sigStart, false);

var exprRangeImplicitOpen = revParser.GetExpressionRange(1, out paramIndex, out sigStart, false);

The values of exprRangeNoImplicitOpen and exprRangeImplicitOpen are best described by example. Consider the following code:

def f(a, b, c):

if a == b and b != c:

return (a +

b * c

+ 123)

while a < b:

a = a + c

When parsing starts at the end of line 4, exprRangeNoImplicitOpen will reference the span containing b * c, since that is a complete expression (remembering that the parser does not know it is inside parentheses). exprRangeImplicitOpen is initialised with one open grouping, so it will reference (a + b * c. However, if we start parsing at the end of line 7, exprRangeNoImplicitOpen will reference a + c while exprRangeImplicitOpen will be null, since an assignment within a group would be an error.

Using the two expressions, we can create a new set of indentation rules:

- If

exprRangeImplicitOpenwas found,exprRangeNoImplicitOpenwas not (or is different toexprRangeImplicitOpen), and the expression starts with an open grouping ((,[or{), we are inside a set of brackets.- In this case, we match the indentation of the brackets + 1, as on line 2 of the earlier example.

- Otherwise, if

exprRangeNoImplicitOpenwas found and it is preceded by areturnorraise,breakorcontinuestatement, OR if the last token is one of those keywords, the previous line must be one of those statements.- In this case, we copy the indentation and reduce it by one level for the following line.

- Otherwise, if both ranges were found, we have a valid expression on one line and one that spans multiple lines.

- This occurred in the example shown above.

- In this case, we find the lowest indentation on any line of the multi-line expression and use that.

- Otherwise, if the last non-newline character is a colon, we are at the first line of a new block.

- In this case, we copy the indentation and increase it by one level.

These rules are implemented on lines 105 through 143 of AutoIndent.cs. However, with this approach there are many cases that need special handling. Most of the above ‘rules’ are the result of these being discovered. For example, issue 157 goes through a lot of these edge cases, and while most of them were resolved, it remained a less-than-robust algorithm. The alternative approach, described below, was added to handle most of these issues directly rather than as workarounds.

Forward Indent Detection

This algorithm replaced the reverse algorithm for PTVS 1.0 and has been used since with very minor modifications. It potentially sacrifices some performance in order to obtain more consistent results, as well as being able to support a slightly wider range of interesting rules. The discussion here is based on the implementation as of changeset 4db951c455d5; full source at AutoIndent.cs.

For this algorithm, the reverse expression parser remains but is used slightly differently. Its definition was changed slightly to allow external code to enumerate tokens from it (by adding an IEnumerable<ClassificationSpan> implementation) and its IsStmtKeyword() method was made public. This allows AutoIndent.GetLineIndentation() to perform its own parsing:

var tokenStack = new System.Collections.Generic.Stack<classificationspan>();

tokenStack.Push(null); // end with an implicit newline

bool endAtNextNull = false;

foreach (var token in revParser) {

tokenStack.Push(token);

if (token == null && endAtNextNull) {

break;

} else if (token != null &&

token.ClassificationType == revParser.Classifier.Provider.Keyword &&

ReverseExpressionParser.IsStmtKeyword(token.Span.GetText())) {

endAtNextNull = true;

}

}

The result of this code is a list of tokens leading up to the current location and guaranteed to start from outside any grouping. Depending on the structure of the preceding code, this may result in quite a large list of tokens; only a statement that can never appear in an expression will stop the reverse parse. This specifically excludes if, else, for and yield, which can all appear within expressions, and so all tokens up to the start of the method or class may be included. This is unfortunate, but also required to make guarantees about the parser state without parsing the entire file from the beginning (which is the only other known state).

Since the parser state is known at the first token, we can parse forward and track the indentation level. The algorithm now looks like this as we visit each token in order (by popping them off of tokenStack):

- At a new line, set the indentation level to however many spaces appear at the start of the line.

- At an open bracket, set the indentation level to the column of the bracket plus one and remember the previous level.

- This ensures that if we reach the end of the list while inside the group, our current level lines up with the group and not the start of the line.

- At a close bracket, restore the previous indentation level.

- This ensures that whatever indentation occurs within a group, we will use the original indentation for the line following.

- At a line continuation character (a backslash at the end of a line), skip ahead until the end of the entire line of code.

- If the token is a statement to unindent after (

returnand friends), set a flag to unindent.- This flag is preserved, restored and reset with the indentation level.

- If the token is a colon character and we are not currently inside a group, set a flag to add an indent.

- And, if the following token is not an end-of-line token, also set the unindent flag.

After all tokens have been scanned, we will have the required indentation level and two flags indicating whether to add or remove an indent level. These flags are separate because they may both be set (for example, after a single-line if statement such as if a == b: return False). If they don’t cancel each other out, then an indent should be added or removed to the calculated level to find where the next line should appear:

indentation = current.Indentation +

(current.ShouldIndentAfter ? tabSize : 0) -

(current.ShouldDedentAfter ? tabSize : 0);

The implementation of this algorithm uses a LineInfo structure and a stack to manage preserving and restoring state:

private struct LineInfo {

public static readonly LineInfo Empty = new LineInfo();

public bool NeedsUpdate;

public int Indentation;

public bool ShouldIndentAfter;

public bool ShouldDedentAfter;

}

And the structure of the parsing loop looks like this (edited for length):

while (tokenStack.Count > 0) {

var token = tokenStack.Pop();

if (token == null) {

current.NeedsUpdate = true;

} else if (token.IsOpenGrouping()) {

indentStack.Push(current);

...

} else if (token.IsCloseGrouping()) {

current = indentStack.Pop();

...

} else if (ReverseExpressionParser.IsExplicitLineJoin(token)) {

...

} else if (current.NeedsUpdate == true) {

current.Indentation = GetIndentation(line.GetText(), tabSize)

...

}

if (ShouldDedentAfterKeyword(token)) {

current.ShouldDedentAfter = true;

}

if (token != null && token.Span.GetText() == ":" && indentStack.Count == 0) {

current.ShouldIndentAfter = true;

current.ShouldDedentAfter = (tokenStack.Count != 0 && tokenStack.Peek() != null);

}

}

A significant advantage of this algorithm over the reverse indent detection is its obviousness. It is much easier to follow the code for the parsing loop than to attempt to interpret the behaviour and interactions inherent in the reverse algorithm. Further, modifications can be more easily added because of the clear structure. For example, the current behaviour indents the contents of a grouping to the level of the opening token, but some developers prefer to only add one indent level and no more. With the reverse algorithm, finding the section of code requiring a change is difficult, but the forward algorithm has an obvious code path at the start of groups.

Summary

Smart indentation allows Python Tools for Visual Studio to assist the developer by automatically indenting code to the level it is usually required at. Since Python uses white-space to define scopes, much like C-style languages use braces, this makes writing Python code simpler and can reduce “inconsistent-whitespace” errors. Language services provide this feature by exporting (through MEF) an implementation of ISmartIndentProvider. This post looked at two algorithms for determining the required indentation based on the preceding code, the latter of which shipped with PTVS 1.0.