Category: Python

I know I’m far from the only person who has opined about this topic, but figured I’d take my turn.

A while ago I hinted on Twitter that I have Thoughts(tm) about the future of Python, and while this is not going to be that post, this is going to be important background for when I do share those thoughts.

If you came expecting a well researched article full of citations to peer-reviewed literature, you came to the wrong place. Similarly if you were hoping for unbiased and objective analysis. I’m not even going to link to external sources for definitions. This is literally just me on a soap box, and you can take it or leave it.

I’m also deliberately not talking about CPython the runtime, pip the package manager, venv the %PATH% manipulator, or PyPI the ecosystem. This post is about the Python language.

My hope is that you will get some ideas for thinking about why some programming languages feel better than others, even if you don’t agree that Python feels better than most.

Need To Know

What makes Python a great language? It gets the need to know balance right.

When I use the term “need to know”, I think of how the military uses the term. For many, “need to know” evokes thoughts of power imbalances, secrecy, and dominance-for-the-sake-of-dominance. But even in cases that may look like or actually be as bad as these, the intent is to achieve focus.

In a military organisation, every individual needs to make frequent life-or-death choices. The more time you spend making each choice, the more likely you are choosing death (specifically, your own). Having to factor in the full range of ethical factors into every decision is very inefficient.

Since no army wants to lose their own men, they delegate decision-making up through a series of ranks. By the time individuals are in the field, the biggest decisions are already made, and the soldier has a very narrow scope to make their own decisions. They can focus on exactly what they need to know, trusting that their superiors have taken into account anything else that they don’t need to know.

Software libraries and abstractions are fundamentally the same. Another developer has taken the broader context into account, and has provided you - the end-developer - with only what you need to know. You get to focus on your work, trusting that the rest has been taken care of.

Memory management is probably the easiest example. Languages that decide how memory management is going to work (such as through a garbage collector) have taken that decision for you. You don’t need to know. You get to use the time you would have been thinking about deallocation to focus on your actual task.

Does “need to know” ever fail? Of course it does. Sometimes you need more context in order to make a good decision. In a military organisation, there are conventions for requesting more information, ways to get promoted into positions with more context (and more complex decisions), and systems for refusing to follow orders (which mostly don’t turn out so well for the person refusing, but hey, there’s a system).

In software, “need to know” breaks down when you need some functionality that isn’t explicitly exposed or documented, when you need to debug library or runtime code, or just deal with something not behaving as it claims it should. When these situations arise, not being able to incrementally increase what you know becomes a serious blockage.

A good balance of “need to know” will actively help you focus on getting your job done, while also providing the escape hatches necessary to handle the times you need to know more. Python gets this balance right.

Python’s Need To Know levels

There are many levels of what you “need to know” to use Python.

At the lowest level, there’s the basic syntax and most trivial semantics of assignment, attributes and function calls. These concepts, along with your project-specific context, are totally sufficient to write highly effective code.

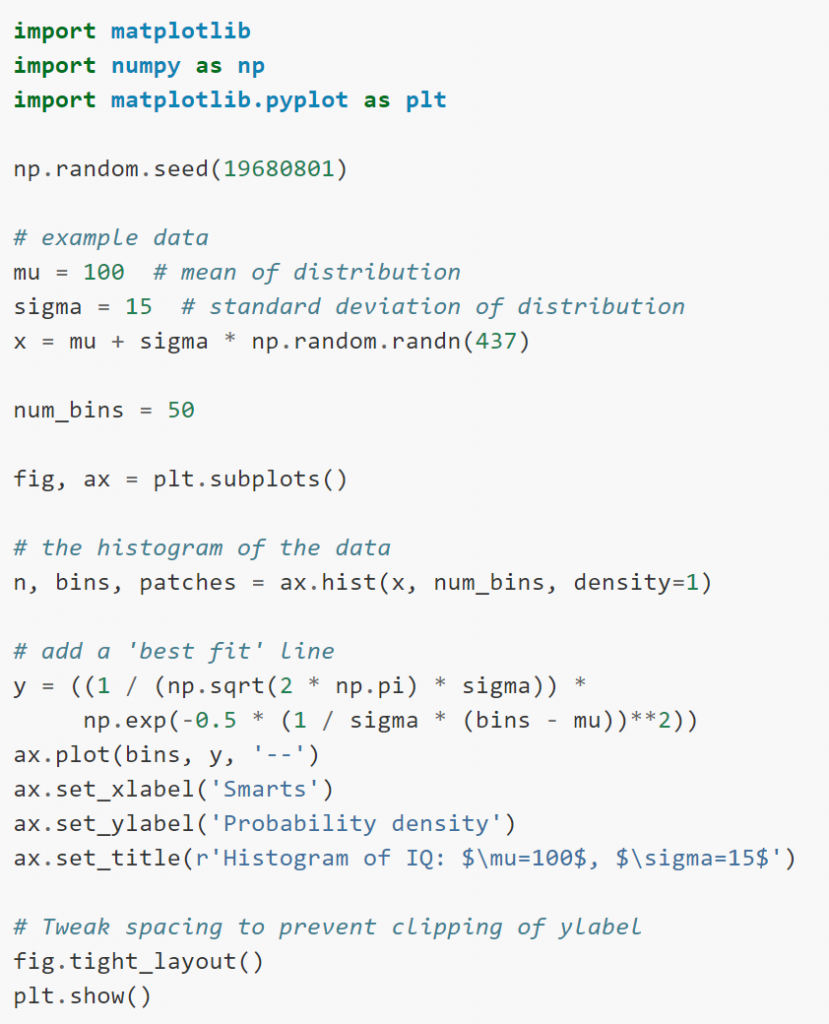

The example to the right (source) generates a histogram from a random distribution. By my count, there are only two distinct words that are not specific to the task at hand (“import” and “as”), and the places they are used are essentially boiler-plate - they were likely copied by the author, rather than created by the author. Everything else in the sample code relates to specifying the random distribution and creating the plot.

The most complex technical concept used is tuple unpacking, but all the user needs to know here is that they’re getting multiple return values. The fact that there’s really only a single return value and that the unpacking is performed by the assignment isn’t necessary or useful knowledge.

Find a friend who’s not a developer and try this experiment on them: show them

x, y = get_points()and explain how it works, without ever mentioning that it’s returning multiple values. Then point out thatget_points()actually just returns two values, andx, y =is how you give them names. Turns out, they won’t need to know how it works, just what it does.

As you add introduce new functionality, you will see the same pattern repeated. for x in y: can (and should) be explained without mentioning iterators. open() can (and should) be explained without mentioning the io module. Class instantiation can (and should) be explained without mentioning __call__. And so on.

Python very effectively hides unnecessary details from those who just want to use it.

Think about basically any other language you’ve used. How many concepts do you need to express the example above?

Basically every other language is going to distinguish between declaring a variable and assigning a variable. Many are going to require nominal typing, where you need to know about types before you can do assignment. I can’t think of many languages with fewer than the three concepts Python requires to generate a histogram from a random distribution with certain parameters (while also being readable from top to bottom - yes, I thought of LISP).

When Need To Know breaks down

But when need to know starts breaking down, Python has some of the best escape hatches in the entire software industry.

For starters, there are no truly private members. All the code you use in your Python program belongs to you. You can read everything, mutate everything, wrap everything, proxy everything, and nobody can stop you. Because it’s your program. Duck typing makes a heroic appearance here, enabling new ways to overcome limiting abstractions that would be fundamentally impossible in other languages.

Should you make a habit of doing this? Of course not. You’re using libraries for a reason - to help you focus on your own code by delegating “need to know” decisions to someone else. If you are going to regularly question and ignore their decisions, you completely spoil any advantage you may have received. But Python also allows you to rely on someone else’s code without becoming a hostage to their choices.

Today, the Python ecosystem is almost entirely publicly-visible code. You don’t need to know how it works, but you have the option to find out. And you can find out by following the same patterns that you’re familiar with, rather than having to learn completely new skills. Reading Python code, or interactively inspecting live object graphs, are exactly what you were doing with your own code.

Compare Python to languages that tend towards sharing compiled, minified, packaged or obfuscated code, and you’ll have a very different experience figuring out how things really (don’t) work.

Compare Python to languages that emphasize privacy, information hiding, encapsulation and nominal typing, and you’ll have a very different experience overcoming a broken or limiting abstraction.

Features you don’t Need To Know about

In the earlier plot example, you didn’t need to know about anything beyond assignment, attributes and function calls. How much more do you need to know to use Python? And who needs to know about these extra features?

As it turns out, there are millions of Python developers who don’t need much more than assignment, attributes and function calls. Those of us in the 1% of the Python community who use Twitter and mailing lists like to talk endlessly about incredibly advanced features, such as assignment expressions and position-only parameters, but the reality is that most Python users never need these and should never have to care.

When I teach introductory Python programming, my order of topics is roughly assignment, arithmetic, function calls (with imports thrown in to get to the interesting ones), built-in collection types, for loops, if statements, exception handling, and maybe some simple function definitions and decorators to wrap up. That should be enough for 90% of Python careers (syntactically - learning which functions to call and when is considerably more effort than learning the language).

The next level up is where things get interesting. Given the baseline knowledge above, the Python’s next level allows 10% of developers to provide the 90% with significantly more functionality without changing what they need to know about the language. Those awesome libraries are written by people with deeper technical knowledge, but (can/should) expose only the simplest syntactic elements.

When I adopt classes, operator overloading, generators, custom collection types, type checking, and more, Python does not force my users to adopt them as well. When I expand my focus to include more complexity, I get to make decisions that preserve my users’ need to know.

For example, my users know that calling something returns a value, and that returned values have attributes or methods. Whether the callable is a function or a class is irrelevant to them in Python. But compare with most other languages, where they would have to change their syntax if I changed a function into a class.

When I change a function to return a custom mapping type rather than a standard dictionary, it is irrelevant to them. In other languages, the return type is also specified explicitly in my user’s code, and so even a compatible change might force them outside of what they really need to know.

If I return a number-like object rather than a built-in integer, my users don’t need to know. Most languages don’t have any way to replace primitive types, but Python provides all the functionality I need to create a truly number-like object.

Clearly the complexity ramps up quickly, even at this level. But unlike most other languages, complexity does not travel down. Just because some complexity is used within your codebase doesn’t mean you will be forced into using it _everywhere _throughout the codebase.

The next level adds even more complexity, but its use also remains hidden behind normal syntax. Metaclasses, object factories, decorator implementations, slots, __getattribute__ and more allow a developer to fundamentally rewrite how the language works. There’s maybe 1% of Python developers who ever need to be aware of these features, and fewer still who should use them, but the enabling power is unique among languages that also have such an approachable lowest level.

Even with this ridiculous level of customisation, the same need to know principles apply, and in a way that only Python can do it. Enums and data classes in Python are based on these features, but the knowledge required to use them is not the same as the knowledge required to create them. Users get to focus on what they’re doing, assisted by trusting someone else to have made the right decision about what they need to know.

Summary and foreshadowing

People often cite Python’s ecosystem as the main reason for its popularity. Others claim the language’s simplicity or expressiveness is the primary reason.

I would argue that the Python language has an incredibly well-balanced sense of what developers need to know. Better than any other language I’ve used.

Most developers get to write incredibly functional and focused code with just a few syntax constructs. Some developers produce reusable functionality that is accessible through simple syntax. A few developers manage incredible complexity to provide powerful new semantics without leaving the language.

By actively helping library developers write complex code that is not complex to use, Python has been able to build an amazing ecosystem. And that amazing ecosystem is driving the popularity of the language.

But does our ecosystem have the longevity to maintain the language…? Does the Python language have the qualities to survive a changing ecosystem…? Will popular libraries continue to drive the popularity of the language, or does something need to change…?

(Contact me on Twitter for discussion.)